If you wake up early enough on a spring day to take the 7:15 am train from Parma towards Brescia, you’ll find yourself captivated by the swift passing of pastel-colored wildflowers, and maybe even catch rare scenes of boar scattering deer across the prairie.

It’s an intoxicating image, and feels as though life and color are being splattered onto the prairie’s green canvas at 100 mph.

If you wake up early enough on a fall day to take the 7:15 am train from Parma towards Brescia, you might expect to see spring’s vivacious portrait mirrored in hues of orange, red, yellow, and brown, but trust that the only pigment and image you’ll see is a yawning cloud of gray.

It is always a bit jarring to see my reflection in the train window suddenly sporting a dense cloak of fog on the first real day of fall in Parma, but I greet this fog with an American fondness for all things spooky (I like to imagine on these days that the train is no longer heading towards Brescia, but somewhere between Transylvania and the Twilight Zone).

The Parmensi (residents of the Parma providence), however, tend to welcome the fog with affection and a great sense of pride.

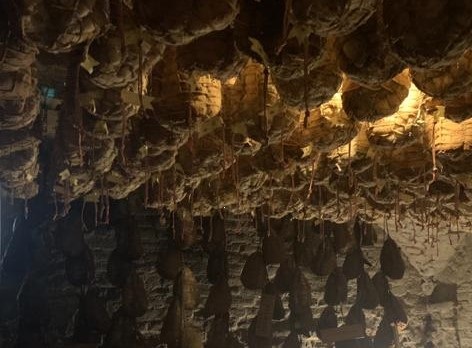

It receives this kind of homecoming year after year because it is a prominent characteristic of the bassa pianura, and is credited for fostering conditions to mature one of Italy’s most celebrated salume: the culatello.

Culatello di Zibello PDO is a delicacy made from the upper part of the pork’s leg stuffed into the pork’s bladder, bound by twine and hung in a cellar during these foggy periods, so as to produce the moldy exteriors that give the culatello its distinct flavor.

It is fatty, mouth-watering and maintains an almost dissoluble quality when placed on the tongue.

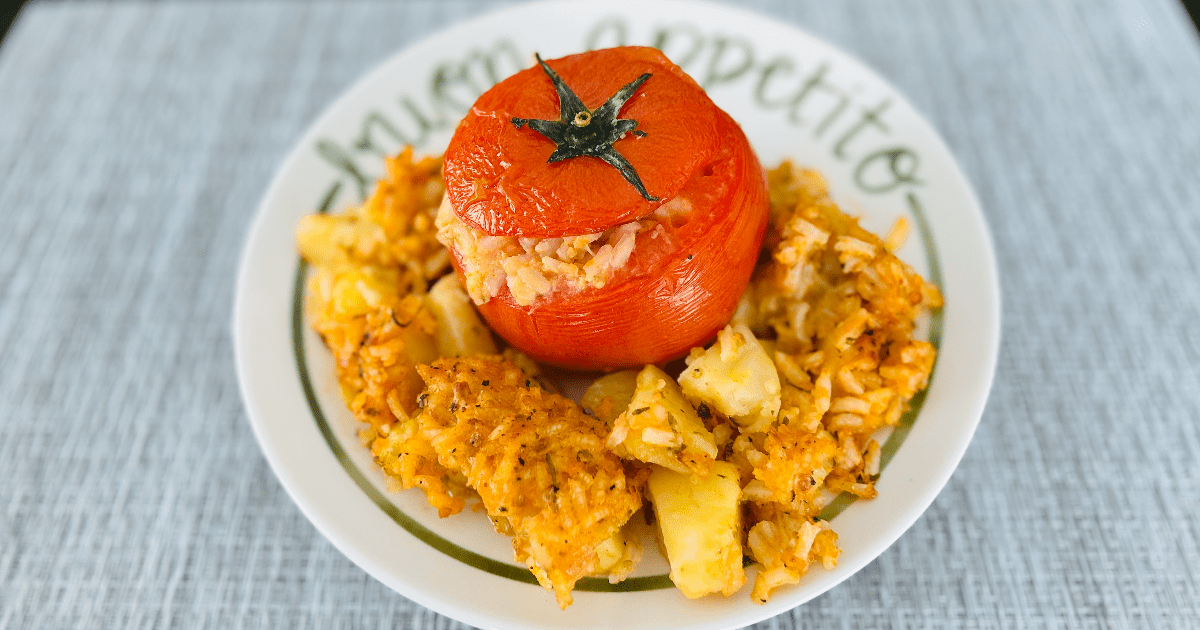

Although the culatello arrives in the first act of a Parmense meal, usually alongside Prosciutto di Parma PDO, Salume di Felino PDO, and a basket full of torta fritta (think: savory New Orleans beignet), it quite often proves to be the meal’s capstone.

We can assume that the fog is not only celebrated for culatello-maturing conditions, but also because it grants a more comfortable weather in which to indulge in the depths and intricacies of the cucina Parmense at large, as the cuisine is considered quite heavy for the summer heat.

Large servings of tris di tortelli (pasta filled with local herbs, potatoes or pumpkin, and bathed in butter) followed by bowls of anolini in brodo (pasta filled with beef, placed into a bowl of beef broth and sometimes topped with a spoonful of Lambrusco) have an undeniable match with Parma’s gray season.

I like to think that perhaps Parma is less Twilight Zone-esque in the fall morning, with the gray-blanketed bassa pianura landscape, than it is at night, with scenes of the Parmensi, beginning their meal with culatello on torta fritta and finishing with a bowl of anolini in brodo, macchiato Lambrusco, proudly shrouded in their cloaks of fog.