Stefano Secchi is the Chef and Co-owner of Rezdôra and Massara in New York City. The former, opened in 2019 in the Flatiron District, is a highly acclaimed osteria inspired by the cuisine of Emilia-Romagna which has received a coveted 3-star review from The New York Times, a Michelin-star every year since 2021 and was recently named the 4th best Italian restaurant in the world by 50 Top Italy. Massara was opened in 2024 with a focus on the cuisine of Campania. Originally in Flatiron, as well, the restaurant was forced to relocate to Park Avenue S. after a kitchen fire. I sat down with Chef Stefano at the temporary Massara location for a wide-ranging conversation about his culinary journey.

Can you tell us about your background?

I was born here, but my parents are both immigrants. My dad is from Sardinia, Italy, and my mom is from England. They met working on a European cruise line and moved to America together to open a restaurant in West Lake Village, north of LA. They didn't like the people there, so they decided to move. They decided on Texas because it reminded my dad most of the flat areas in Sardinia, which I find funny. They ended up moving there in 1982 to open a restaurant, and my two younger brothers and I grew up in Dallas, of all places.

I’m guessing you were the only kid in your school named Stefano…

Of course! No one had any idea how to pronounce my last name either. It was unbelievable. I used to bring anitpasti to school, and I guess that was weird, too.

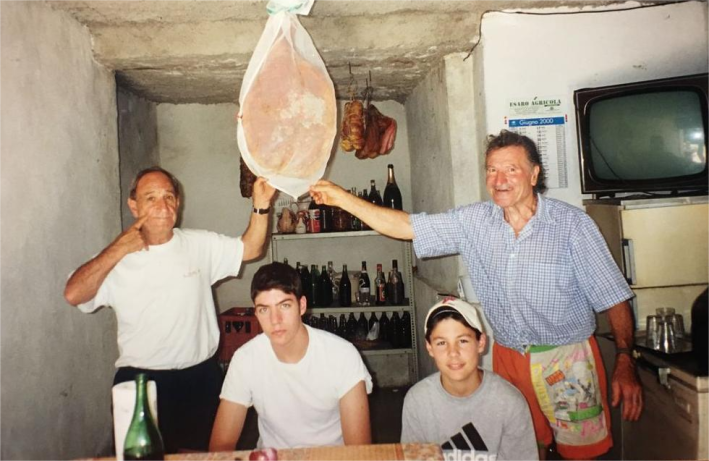

But it was fine. I had a great childhood, but it was different because I never really understood American sports. My dad only wanted us to play soccer, and soccer was nowhere near popular in Texas back then. There was really only football, basketball, and baseball. And then, every year, we would spend six or seven months going to school, and the other months in Italy, so we wouldn't have any summer in the States, which sucked for us because when you're young, you want to spend time in the summer with your friends. You want to go to the pool and play sports. We spent all summer in Italy. My dad's first chef, whom we called "Uncle Dino," was from the Campania/Calabria border, so we used to fly into Calabria and then go to Campania. We’d go fishing in the morning and then, you know Italy, and especially the south, we’d spend all day worrying about what we were going to eat for breakfast, lunch and dinner. After a few months, we’d go to Sardinia for the rest of the summer.

Was the restaurant your parents’ owned rooted in the cuisines of Sardinia, Campania, and Calabria?

No. They tried to do Cibo Classico Italiano, Peninsula-based, greatest hits from the 20 regions, but they couldn’t. This was Texas in 1982. People didn't want to eat Risotto Nero di Sepia. People didn't want to eat Vitello Tonnato. They didn't understand these things, so my parents segued to more Italian American cuisine. Chicken Parmigiana. Spaghetti Polpette. Fettucine Alfredo was a thing. Stuff like that. Those dishes were very popular back then, so we had them on the menu, and people kept coming. I was much more inclined to eat cibo italiano, regional Italian, because of spending the summers there, but when we were back in the States, we were doing Italian American, no question, with the exception of Lasagna Bolognese Classico for Christmas, which we would make at home. Those things were difficult for my dad to digest. He was always front of the house, and his first chef was super Campania, super Calabria, so peperoncini would be in there, all these types of sauces, like Puttanesca, Pizzaiola, but the mainstays were the Chicken Parmigiano, the Fettucine Alfredo, the Spaghetti Polpette, because that was the way to keep the doors open.

When did you start working at the restaurant?

I started at 12, super young. The place was busy, but not too busy, and I’d work three or four days during the week. My parents were never around at night, so it was a chance to be with them, which was very important because it’s that weird age where you want to be with them, but you kind of don't because you want to be with your friends, but I wanted to see them at night, so we used to have dinners together every night, whether I was working or not. That was beautiful, and I’d never trade that for anything.

When you were working at the restaurant, what did you do?

At first, I would prep and then go do a round of dishes and then prep some more. Eventually, I moved just to prep, and I became really good with a knife. When I graduated high school, my parents wanted me to go right to college. I told them I wanted to cook, and that pissed them off. So, we had a career fair at my high school, and CIA [Culinary Institute of America] was recruiting there for some reason, I have zero idea why. I was the only student to go to them, and that was the only place I applied. At that time, CIA, I guess, was kind of difficult to get into, but I had the experience and not amazing grades but good enough. I got a scholarship from them, which was great because my parents told me I had to pay for everything.

How was CIA?

That experience was amazing because it was the first time in my life where I was sitting in class and my notebooks were totally full. I couldn't get enough. I went to school to cook every day, which I was pretty good at anyway. So for me, it was the best. Through them, I was able to work in the city for about a year and a half at Felidia. And then my parents finally convinced me, more like told me, I had to get an undergraduate degree and a regular job before deciding if I wanted to cook full time. So, I went back down to Texas and attended SMU [Southern Methodist University]. I graduated in three and a half years with a degree in Economics. I got a job in corporate America, banking at Bear Sterns up here in New York.

How did it go in corporate America?

You have to understand, being the child of immigrants is very hard to describe to people unless you've been to a place where things in life are just difficult. I had student loans. My parents didn't pay for anything. And I'd been working since I was 12 years old, and so those types of places, like Bear Sterns, love to hire people like me because all I wanted to do was work. I didn't care about social life, really. I mean, yeah, I’d go out and do those things, but all I wanted to do most of all was work. I had no guidance from my parents. My dad was a farmer from Sardinia. My mom's dad was a butcher, and so she grew up in pubs. Usually your father and or mother guide you through life, but I had to learn by myself or through my friends, and so when it came to getting jobs, or anything I was doing, I was very competitive because I felt that nothing was really ever given to you and it could be taken away in no time. It was about economic stability, so I was extremely competitive. That drive still exists.

And then what happened?

Well, I made money, but the paycheck was never the most important thing to me. At the end of the week, I really didn’t care. I wanted to go back to cooking really bad, and I told my parents that I was finished with corporate life. I moved to California and worked with Nancy Silverton at Osteria Mozza in Santa Monica for a couple of years before deciding that it was important for me to go to Italy. So, I just left and moved to Emilia-Romagna to live full time. I didn't know anyone there at the time, but I had a passport and I could work.

When was this and why Emilia-Romagna?

It was 2012, and the reason I chose Emilia-Romagna is because of the holy trinity of Italian food - Parmigiano Reggiano, Prosciutto di Parma, and Aceto Balsamico - all come from that region. Also, when I was younger, my father and my two brothers and I were driving to see my aunt and uncle in Milano, and we stopped off outside of Bologna, and I had Tortellini in Brodo for my first time. That experience made me want to be a cook and to focus on cibo italiano for the rest of my life. For me, it was a no brainer.

Where in the region did you settle?

Bologna was a little intimidating to me because it was so big, and Modena felt a little more manageable. I was staying in a little bed and breakfast, and over the first three weeks, I ate at 30 different places, except for this one place, which was only open for lunch, the oldest salumeria in Europe called Hosteria Giusti. They only had four tables and didn’t take reservations. I walked in every day, and they kept telling me they were booked, until one day I got in because someone had canceled last minute. I sat down and ordered every primi on the menu, and, of course, the antipasti of Gnocco Fritto and Cotechino Fritto con Sorbara Zabaione. Every pasta was incredible, but the Tagliolini con Asparagi e Burro di Parmigiano was the one that blew my mind. The texture was incredible. There are probably four ingredients to that whole pasta. I had every other pasta they had on the menu that day and came to eat two or three more times. I asked if I could come work with them. Nonna Laura Morandi was running the kitchen at the time, and she said no. I kept coming back to ask if I could work there, and she kept saying no. Finally, after a fourth time, she said if I stopped bothering her, I could start in April.

I worked there for lunch and at Antica Moka at night for about a year and a half. Moka was similar to Giusti in that it had nonnas in charge, but there were more tables and staff. There was one girl and one guy that I started becoming friendly with while working in the kitchen at Moka. There were from ALMA, the famous cooking school of Italy in Parma. In the meantime, I heard about Massimo Bottura and his Osteria Francescana in Modena. I would walk by there and think that it would be a nice place to work. I sent my resume to the office manager, and he said he’d get back to me, but months went by without a word.

A guy I worked with at Moka was from Piemonte. He’d go back every weekend, and I went with him once. We ate at this place, All'Enoteca, a one [Michelin] star restaurant in Canale, just outside of Alba. The owner and chef was Davide Palluda. I’d eaten at [Michelin] starred restaurants in Italy before, but there was nothing like this. I was like, “Holy shit.” I had to find a way to work with this guy, so I asked him right there and then. He said I could come over as soon as I was done in Modena.

When I was done in Modena, I rented a small apartment in Canale and just went to work. We did everything. That was an amazing experience, though very hard because the sous chef was an asshole, but I like busting my ass. We had a great time, 12-hour, 14-hour days, six days a week. When the Fiera del Tartufo [white truffle fair] came around, we worked six and a half days out of seven with only Sunday nights off. The hours were really intense, but I learned classic Piemontese cuisine with a contemporary eye. Davide is fantastic, and he became an amazing mentor, and we've kept in touch ever since. While I was there, I ended up getting an email from the manager at Francescana who wanted to know if I could start in August.

I moved back to Modena and started with Massimo. The reasons I was able to work with Massimo are because I can speak both languages, I had legal citizenship, and I also knew how to roll sfoglia [sheets of pasta] for tagliatelle using a mattarello [a traditional, long Italian rolling pin]. Using a mattarello is kind of a dying art, but I had so much experience rolling sfoglia at Giusti under the tutelage of Nonna Laura Moranda, so that was my value added right there. I would get there in the morning and roll out the day’s pasta. Then I’d work antipasto and eventually worked through all of the stations. For almost two years, I was in that kitchen almost every single day, even though we we're only open five out of seven. At that point, we were ranked third [best restaurant] in the world, and we had the three [Michelin] stars But it was completely different because Massimo was very convivial and very familiar, so it’s a work environment where you're super proud and happy to be there. And that works for me. I push it more when I'm in that environment. There was a time before where I started getting a little bit burnt out, but I wanted to be with Massimo and our team all the time. That type of environment was eye opening.

Aside from the contemporary Emilia-Romagna cuisine, I learned that you could run a kitchen where it's very convivial, where you hold super high standards and people hold themselves accountable, and you push the team to be better for each other and less so for one figure. I will always run kitchens like that. You have extremely high standards. You hold people accountable, but then you say hello to each other, and you shake each other's hands, and you can smile and you feel like you're in a place where people will take care of other people.

When did you leave and why?

Without talking too much about economics, to live in Italy without having a house or something from your parents is extremely tough. So, I had to leave because of that. I still had student loans. I was also at the age where I need to figure out what my next step was going to be. I had been engaged to a woman in Dallas, who had broken off the engagement when I moved to Italy, and she became my fiance again when I moved back to the States. That was good. And I told her that we could go to Los Angeles or New York. LA had better produce but Milan is only six or seven hours from New York, which is amazing as we could do that in a weekend. She said, “OK. We’re going to New York.”

So, we came to New York, and I worked as a cook at Marea. Michael White was still there. They had two [Michelin] stars and really great Italian food. I had just come back from all this time in Italy, and I was like, “God, I just want to be at a place where I can just cook, like I'd been doing in Italy.” I didn’t want an executive chef position. I didn’t want to interview for jobs. I just wanted to cook, so I did. But I’d been talking with a friend I’d met in California, great guy named David Switzer, about doing something together in New York. He was still in LA but wanted to come to New York. Then this opportunity came across to open a small place downtown on 20th Street. I always wanted to be downtown, and we had the chance to open up Rezdôra and offer New York City the traditional cuisine of Emilia-Romagna.

Was it successful right away?

No, not at all. We had around 50, 60 covers per night in the beginning, and I was doing everything. I couldn't get anyone to work for me. We had people in the door, sure, but I was a wreck. I was waking up 4:00 in the morning. I was rolling all the pasta with a matarello first thing. I was doing all the ragus, all the braises, all the repieni [stuffing of the pastas], all the prep, everything, for probably the first two months. I’d have everything ready for the cooks when they came in at 2:00. We had no working capital to start, so I couldn't pay them to come earlier, and we couldn't lose money right away. So, I would do all the prep, and then they would come in and set their stations, and then we’d cook service. We were open seven days a week, only for dinner at that time. I didn’t take a day off for three, four months. My wife and I just had a baby, as well, and we were living in a studio apartment with the baby and a dog. I was a wreck.

But then came The Times review…

Yes. It’s funny, but I didn't know anything about this review period. People thought I wasn’t taking time off because I was waiting for the reviewers to come, but none of that was on my radar. I was trying to keep up with the demands of the restaurant. Of course, I was aware that they were coming in and that Pete Wells from The Times had been in for a third time. And after that third time was when I could finally breathe. I took that Sunday off and slept all day. It was unbelievable. My wife made a cup of tea for me. I had an espresso. I was up for two hours, and then I went to sleep again. I woke up the next day and went to work. Of course, we soon got that 3-star review from The Times, and that changed all of our lives as we now had a regular line outside the door at 5:00 p.m. waiting to come in. And we could hire more people.

Tell us about Massara…

David and I opened Massara in June of 2024. The cuisine is very much based on my memories in Campania as a kid with Uncle Dino, my dad’s first chef. Campania is a really important region: Pizza Napoletana, Buffalo Mozzarella, Puttanesca, Genovese. Amazing. We had to adapt the menu after the fire because here, at our temporary location, there is no pizza oven. So, we do much more crudo here. We do carpacci di tonno, hamachi, fluke. Among our best-sellers would be the grilled cibattas we have as an antipasto. We have many of the incredible salads from Campania and Calabria. Pastas, of course, like Genovese, the three-day ragu. That's a best seller, for sure. And then Corteccia which comes from the mountainous Cilento area of Campania. It is a sausage ragu in white sauce with broccoli rabe. We have traditional roasted meats and whole fish.

And we can assume you will get back to the pizzas when you return to the original location?

Yes. We can't wait to do that.

What's your favorite thing about your job?

I don't think it's just one thing now. It's mostly the people that I work with, but I think the bigger picture is more pushing the conversation forward with regard to Italian culture and doing things correctly. That's probably one of the most important things that I could give back to the States. If you're going to borrow from cibo italiano, I think it's really important that we put the names on the menu correctly. I mean, tortelloni vs. tortellini. Both are stuffed pastas, but they are different sizes. If you are going to put them on your menu, you should know the difference. Also, there's no such thing as Lobster Bolognese or Duck Bolognese or Lamb Bolognese. Bolognese is Ragu Bolognese from Bologna. There, it’s just called Ragu. It’s made with beef, pork, and veal, a combination of two or just one, but that’s Bolognese. Everything else is a ragu of duck or lamb or whatever. I love pushing Italian culture forward in the right way in the States. Plus, I get to eat for a living. I mean, How can you go wrong?