I recently found myself in my parents' kitchen, dutifully following a recipe for a new way to cook spinach. While I regularly buy frozen bags of the leafy green, that day I was cooking down a pan of fresh spinach before squeezing out all of the liquid, coarsely chopping it, adding onions, and throwing in a hearty amount of pignolis and raisins. The ingredients were few; the instructions were simple, and the dish was fantastic. Suddenly, I was transported back to having the very same dish a few years back while on a trip to Rome.

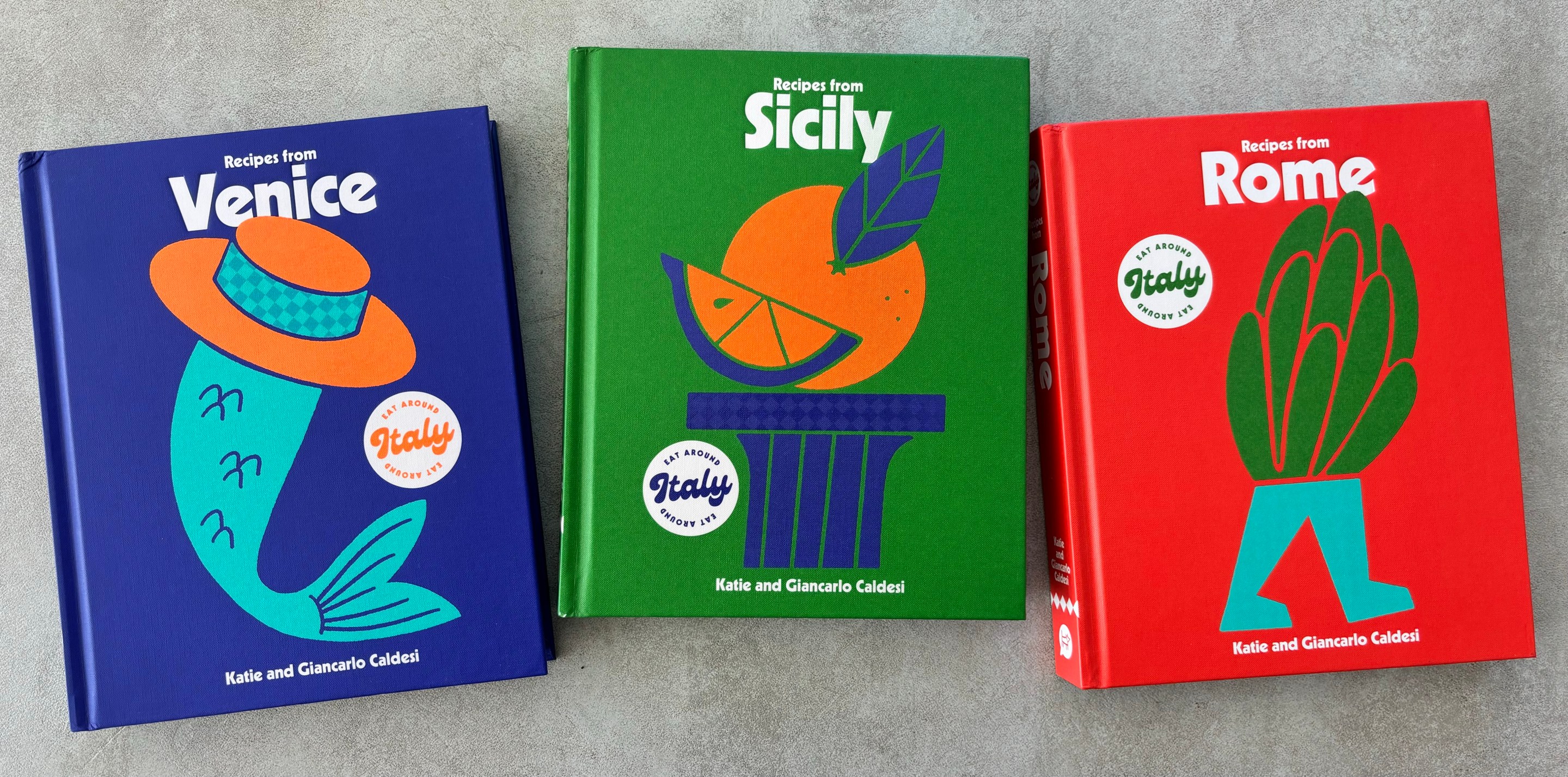

That ability to transport the reader through sensory immersion is the magic of the 15 lip-smacking cookbooks of Katie and Giancarlo Caldesi, food superstars in their native England (where they also operate a cooking school and two popular restaurants). Their series, Eat Around Italy, recently repackaged and released for American readers, focuses, respectively, on Rome, Venice, and Sicily. Each book features the most popular local recipes from the area's most historic restaurants and private homes, amid luscious imagery, sleek design, and poetic writing.

I spoke to Katie for Appetito about Italian cooking, how they managed to convince local restaurants to hand over their most prized recipes, and the process of pulling it all together.

Ciao, Katie! Thanks for chatting with me. Alright, a pretty basic first question: In your estimation, what makes Italian food so special?

In my opinion, it is the concentration on the ingredients which is the star of the show. The freschezza of the fish, the firmness of the mozzarella, the ripeness of the tomato. It’s the fact all of these features are appreciated, highlighted, and not smothered.

Your cookbooks are getting this beautiful American re-release, and you initially zeroed in on Rome, Venice, and Sicily. What makes those regions so notable and unique to start with?

When it comes to the UK version of the series, our book on Amalfi was actually the first we worked on. So many people have visited the coast, but the book was to identify the cooking from that area and put it all into one place as a recognizable cuisine. There is so much more to Amalfi than pizza and fish. Rome got me looking into the past which is still so relevant in the present. In fact, I found it hard to find new, innovative dishes in Rome – even young people chose a dish that was hundreds of years old as their favorite thing to eat.

I love how you include a variety of recipes, some even from the most popular restaurants in each region. How did you manage to get these places to spill the beans on how to make some of their most iconic dishes?

Giancarlo and I developed a way of talking to the locals in shops, restaurants, and hotels to get to know where they ate and what they considered to be the recipes of their region. Then we ate at restaurants without saying who we were and what we were doing. Only when we thought the food was really great did we fess up. 99% of the time they welcomed us into their kitchens. Most people, it seems, love to share their recipes and were delighted to be in a book. One of the nicest things about my job was to go back to the region and hand out the cookbooks once they were printed. People were delighted to be a part of them.

We also talked to our 70-person staff at our restaurants who used to be mainly Italian. Nearly always we would find a relative of theirs to go and visit. Our staff would be so proud of their family recipes they would do what they could to help us. As I look through the books, I can recognize the nonnas and mamas of so many of our staff members.

How long does it take to put together one book, from start to finish?

Around a year from us traveling to the destination multiple times, writing, testing and finalizing the book before publication.

Was there anything that surprised you while you were putting together these books?

What surprised me was the generosity of the people who were passionate about their recipes, restaurants, home kitchen, ingredients and were quite happy to tell us and our readers all about it. They gave their time, and often their food, to us with such Italian warmth and kindness.

What are some of your favorite recipes?

Pasta with sardines and wild fennel sauce from Sicily. Suppli, which are rice and cheese fritters from Rome. And Riccarelli, the almond biscuits from Tuscany.

I’ve had a lot of fun cooking through the books. One of the biggest crowd pleasers was the spinach, raisin, and pine nut side from the Rome book. I remember having that at Vitti in Rome and forgot how amazing it was before I made it. What can you tell me about that dish?

That’s a really interesting one. I was told that the Jews learned to use dried fruit and nuts in cooking from the Arabs in Sicily. Apparently, they lived happily together for 400 years, and their cooking traditions intertwined. Then when the Spanish expelled the Jews in 1492, they took this recipe with them. We once went to Gibraltar for a book festival, and the local Jewish community there cooked this dish of Spinach with Raisins and Pinenuts. Whenever you see this combination, it comes from Sicily.

I also made the sweet and sour aubergine dish, the Caponata, from the Sicily book. It’s so unique, and I know there’s a lot of history to that dish. What are your thoughts on Caponata?

I love it on its own, with cheese or with fish. It’s strong, punchy and beautiful combo of old Jewish and Arabic flavors.

The books also highlight various locals in the respective regions, a beautiful way to zero in on the people behind the cuisine. Where did that idea come from, and do any standout as the most unique characters you’ve come across?

I felt it was really important to get to know the locals and find out what was crucial to them about their cooking, what made it different and peculiar to that region. I made a promise to Giancarlo when I started writing about Italian cookery, 20-odd years ago, that I wouldn’t put an English twist on anything, I would tell it like it is. This meant I wrote an introduction to each recipe saying where it was from and giving tips from the original creator of it. I faithfully copied what they did, often bringing out a set of digital scales, a measuring jug or set of measuring spoons from my handbag to make sure I got the correct proportions.

Italians often cook al occhio (to the eye) or use the term quanto basta (when it’s enough) or use a small wine glass to measure things. That just wasn’t precise enough for me, so I am sure I annoyed them with my measuring tools! Twice we brought a chef back to England to stay in our house and cook with me. There was Sicilian Marco, Tuscan Antonella, and Roman Stefania who came to stay with us. They enjoyed themselves; I certainly loved it and learned loads from them. Looking back, it seems quite odd to ask a stranger to come and stay with you, but, at the time, it seemed a natural follow-up. We are still in touch with them now, and Stefania’s son spent the summer with us this year, and they are coming for Christmas, so we formed plenty of wonderful friendships through putting together these books.

Okay, just so people don’t get too jealous that this is your amazing career, give us a reality check. What are the biggest challenges behind putting together a cookbook?

Choosing what to leave out. I become quite possessive over my discoveries and hate to kill any of my darlings, but I often over-write a book, and an editor has to make the chop.

You opted to not include a cannoli recipe in the Sicily book, explaining it’s impossible to replicate the real thing. What makes cannoli-making so tricky?

You need a mold to shape the pastry around. This could be metal or a piece of cane (hence the name). Then you need to deep-fat fry the pastry cases on the mold and deal with bubbling fat, etc. Then you need to find proper sheep’s milk ricotta for the sourness to balance against the sugar. At that time, I was interviewed by someone from The Guardian that didn’t travel who was doing a piece about dishes. It made me realize I didn’t have to include recipes that failed multiple times. If you like, I took on all the waste of time, of ingredients, of fat splashes instead of the reader. Sometimes a cookbook should pay respect to a dish but not try and make a poor copy of it thousands of miles away from its origin.

Finally, I hate to get too personal here, but here’s a big question! You have to choose one: cannoli, Tiramisu, or an assorted platter of Italian cookies? What are you reaching for?

I actually don’t have a sweet tooth, so can I choose the Pasta Alla Checca Pasta with Raw Sauce from Rome, that gets cooked about 12 times a year in my kitchen. This is a dish of hot spaghetti with a punchy, spicy raw salsa that gets topped with creamy ricotta that melts and melds the rest of the ingredients together; bloody lovely! If not, then I would go for the cookies!